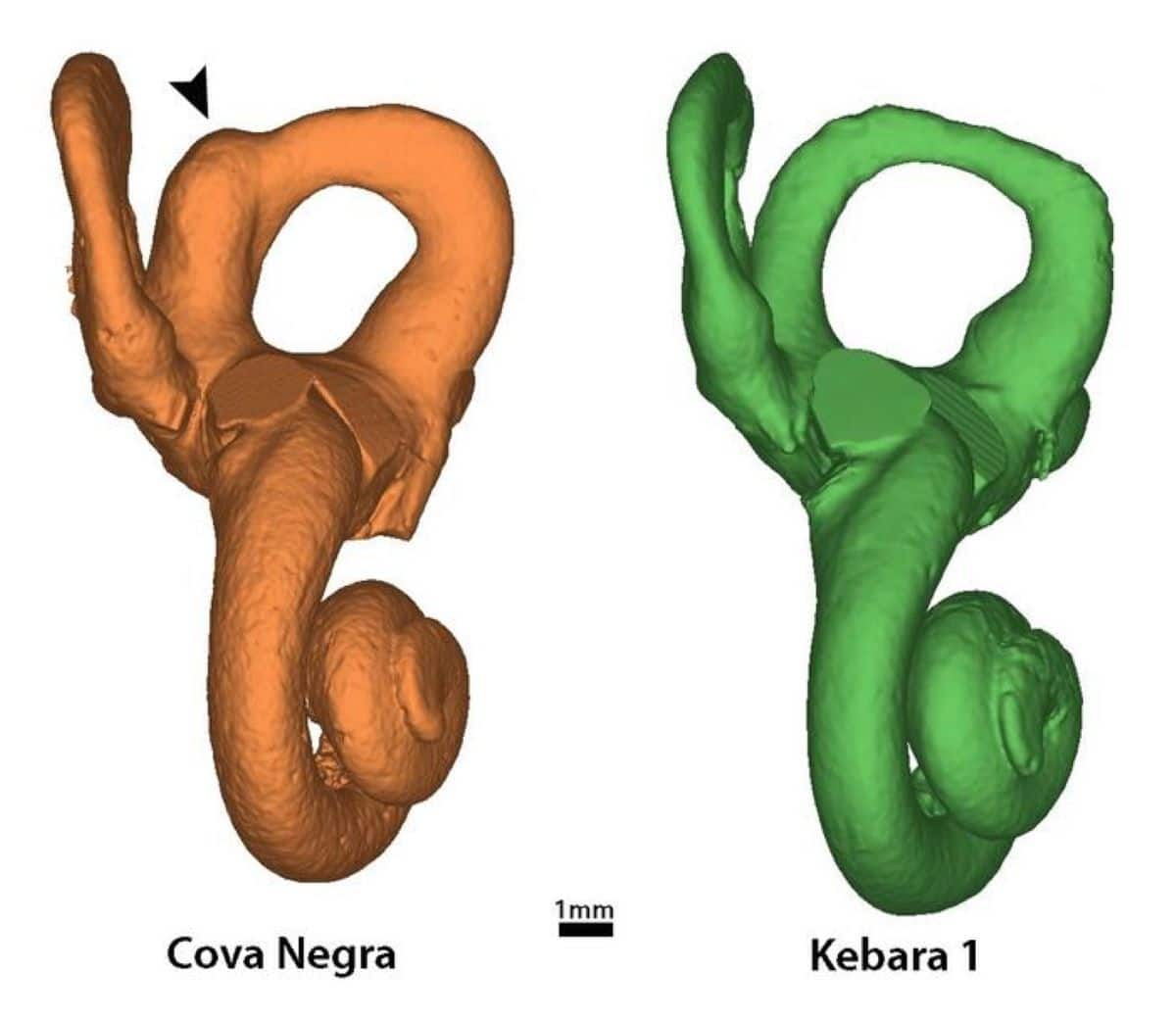

A series of recent discoveries have shed new light on the communal caregiving practices of Neanderthals, as evidenced by the fossilized remains of a child with Down syndrome. The child, named Tina, was discovered in Spain and is estimated to have lived approximately 273,000 years ago. Researchers from various institutions including the University of Alcala in Spain and Binghamton University identified several abnormalities associated with Down syndrome in Tina's inner ear reconstruction from CT scans.

Despite her severe hearing loss, imbalance problems, and vertigo, Tina survived to at least 6 years old. This remarkable feat suggests that Neanderthals provided extensive care for this vulnerable member of their social group based on altruism rather than reciprocation.

The demanding lifestyle of Neanderthals would have made it challenging for the mother to provide care alone, and prehistoric children with congenital diseases had an uncertain path to survival. The findings from these studies challenge the theory that caregiving emerged merely as a self-interested pact between participants who could reciprocate the behavior.

The Neanderthals, or Homo neanderthalensis, were known for their big brains and burial practices. They lived during the Paleolithic period from 430,000 to 40,000 years ago. Although they had some differences in skull morphology compared to modern humans, researchers believe that Neanderthals were similar to us in many ways.

The discovery of Tina's fossil adds valuable insights into the compassionate and caring nature of our prehistoric ancestors.