Deep-sea anglerfish are known for their unique reproductive methods, which involve sexual parasitism. In this process, tiny males attach to much larger females to mate. This phenomenon has been a subject of scientific interest due to its implications for the evolution and adaptation of these deep-sea creatures.

According to recent studies published in various journals such as Current Biology, Yale University researchers have shed light on the evolutionary history and significance of sexual parasitism in anglerfish. These studies reveal that this reproductive strategy facilitated their transition from shallow waters to the deep sea during a period of global warming around 50-35 million years ago.

The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum was a time of significant climate change, leading to rapid transitions in various ecosystems. During this period, anglerfish underwent a rapid transition from benthic walkers on the ocean floor to deep-sea swimmers. The loss of adaptive immunity in deep-sea anglerfish groups is thought to have been an advantageous adaptation for inhabiting the deep sea and allowing individuals to latch permanently once they found a mate.

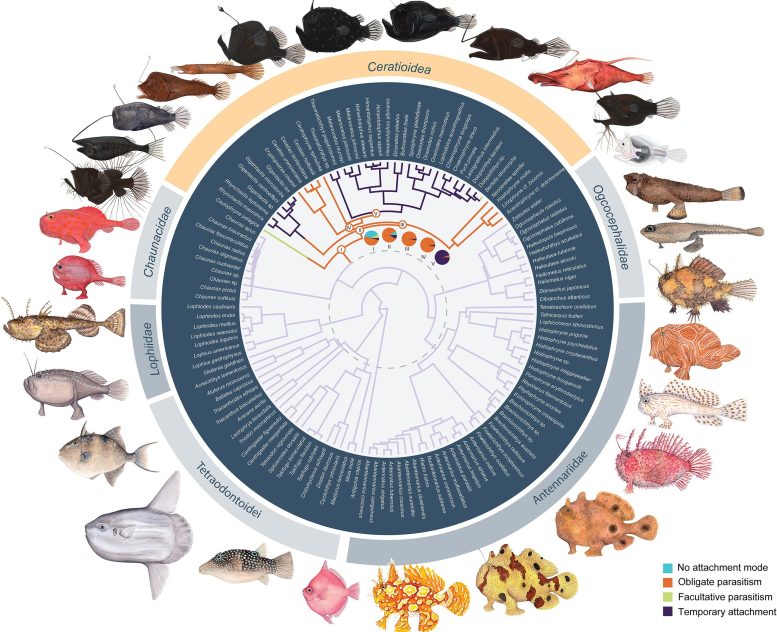

The Yale researchers analyzed fossil evidence and genome-scale DNA sequence data from over 100 species of anglerfish to understand their relationships, ages, and evolutionary history. Their findings suggest that sexual parasitism played a role in the diversification of anglerfish but did not directly cause it.

The deep sea is an expansive ecosystem that covers over 97% of the planet's inhabited space. Finding a mate in such vast open waters can be challenging, making sexual parasitism an effective strategy for these deep-sea creatures to ensure successful reproduction.

In conclusion, the unique reproductive method of sexual parasitism has played a significant role in the evolution and adaptation of deep-sea anglerfish. Their ability to permanently attach to females has facilitated their transition from shallow waters to the deep sea during a time of global warming.