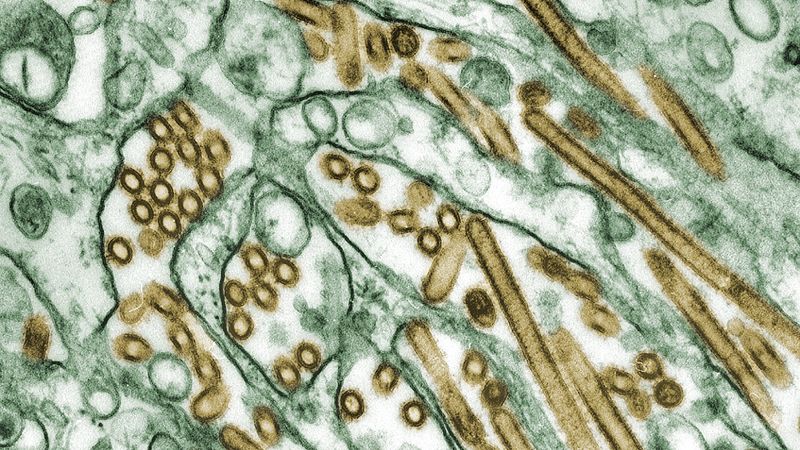

In late March 2024, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) confirmed the presence of H5N1 avian flu in dairy cattle across multiple states. However, new research suggests that this virus had been circulating among these animals for at least four months prior to confirmation.

According to a preprint study led by the USDA National Veterinary Services Laboratory (NVSL), five introductions of the B3.13 genotype from cattle to poultry, one to a raccoon, two to domestic cats, and three to wild birds have been identified.

The findings come as Michigan and Colorado have announced emergency measures in response to the outbreak. In Michigan, dairy farms and commercial poultry farms are required to implement biosecurity steps. Lactating cattle are barred from being displayed until no new detections for 60 days, and interstate movement of lactating cattle is restricted.

Colorado has adopted an emergency rule requiring mandatory testing of lactating cattle moving interstate.

The genetic sequencing findings suggest that asymptomatic cattle movement is likely driving transmission. Scientists have identified about two dozen mutations in the H5N1 virus as it has circulated in dairy cattle, some of which make influenza viruses more deadly or more likely to infect humans.

The USDA study also indicates that there are gaps in data and surveillance, raising the possibility of undetected transmission chains. The researchers suggest that these gaps could be addressed through increased testing and monitoring in affected herds.

The H5N1 virus had been devastating wild and domestic bird populations since 2022, infecting a growing number of mammals. One farmworker who came into contact with infected cows tested positive for H5N1 and recovered. The USDA official confirmation of H5N1 in dairy cows occurred on March 25, 20XX, and at least three dozen infected herds across nine states have been identified.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has advised that pasteurized dairy products are not a risk for transmission. The metagenomic sequencing technique for identifying emerging pathogens is being used to prevent outbreaks in animals leading to human pandemics. Transmission routes include wild birds, cattle, domestic poultry flocks, and raccoons.

Despite the efforts of regulatory bodies and scientists, H5N1 now seems well-entrenched in the dairy cattle population.